Taking your phone into the pool for a quick swim might seem like a great idea – but it’s risky, even if you think you have a waterproof phone — which you actually don’t.

How Do I? covers the basics, because we’ve all got to start somewhere.

A lot of smartphones – and a variety of other tech gear from portable speakers to headphones and more – often sell themselves on having a level of water resistance built into them.

This leads many people to presume that they’re waterproof phones (or other gadgets), and therefore everything from pool swimming to beach jaunts must absolutely be fine, only to discover post-swim that suddenly their $2,000 smartphone just won’t turn on.

That’s because they just inadvertently drowned or shorted out their fancy new waterproof smartphone – an expensive mistake to make.

The mistake here largely is in a misunderstanding between a “waterproof” phone and a “water resistant” phone.

What does waterproof mean?

As Billy Connolly once put it, Wellies keep oot the water, and they keep in the smell… so they’re waterproof!

The literal dictionary definition (they differ a little, but let’s go with the OED definition) is as an adjective, meaning “impervious to water”.

Fun fact: The OED says that the earliest usage of “waterproof” dates back to the 1600s. It’s been around longer than you might think!

For the sake of clarity, “impervious” means “not able to be passed through or penetrated” – so an item that is waterproof would not allow water to pass through it at all.

So a waterproof phone would be one that was impervious to water passing through it, and to the damaging effects of water as a result.

What does water resistant mean?

This is resisting water, not strictly speaking water resistant. Cute puppy, though, innit?

Water resistant is an adjective that means “resistant to the adverse or damaging effects of water; not readily damaged, penetrated, or removed by water”

It’s not an absolutely interchangeable term. A water proof phone is technically one that’s water resistant (and more), but a water resistant phone merely means that it has a level of resistance, not the “impervious” nature of a water proof phone.

The odds are very good that if you buy a smartphone that has anything to say about water in its marketing, it will talk about being water resistant. There’s a whole standard – IP Ratings –that relates to water resistance which I’ll explain in a second, but I may as well complete the trifecta first…

What does water repellent mean?

Most of a duck is water repellent — because they would sink otherwise. But there are areas of the duck where water can easily get in, like the beak.

This one’s the easiest to understand; it means that it has some level of either coating or material property that works at some level to repel water.

For smartphones, “water repellent” is basic table stakes that typically doesn’t mean all that much. The front screen of a smartphone is water repellent – it doesn’t absorb water like a sponge, it rolls off the screen – but in most cases a water repellent phone will have little or no protection on ports or other areas to deal with water ingress. There’s no standards in play, and it’s largely a marketing term with no strictly defined parameters or coverage.

A little light rain on the screen might be OK, but any moisture getting into the charging socket, speaker grille or headphone socket (if it has one) could be ruinous.

IP Ratings explained

When you get a smartphone with any qualified level of water resistance – this involves lab testing, and I’ll get onto that in a minute – it will come with what’s called an IP rating – Ingress Protection – that gives you a quick glance explanation of its likely protective status.

Quick glance if you’re au fait with IP ratings numbers, that is.

Firstly if there’s an X in either the first or second number of an IP rating, it means it has no tested capacity in that field whatsoever; you will sometimes see devices that are (for example) IPX6 or IP6X. Strictly speaking, a completely untested device could be called an IPXX device, though nobody would practically bother with that.

The first number in an IP rating relates to dust ingress, and for the most part you’ll find IP-rated smartphones and other tech gear tends to have that first rating as 6 – the highest level, full dust ingress protection – though sometimes you’ll see an IP5 rated product in the market, meaning that it has a level of dust protection. First digit numbers lower than 5 refer to other larger objects and insect ingress, neither of which are desirable in a smartphone. Don’t go shoving screws or fire ants into your phone, OK?

Water ingress is covered by that second number, with varying levels of water covered. I’m going to be a tad lazy here and use Wikipedia’s IP Code table here to save myself writing it all out again – as a side note I’ve written more than a few pieces on IP ratings over the years, and writing out IP code tables is somewhat tedious work.

That’s probably more about IP rating terminology than you figured you need to know, but it does show a few very key factors to bear in mind.

So if I’ve got an IP68-rated phone or gadget, I’m good to go jumping in a pool or go scuba diving, right?

Swimming in the pool is wise. Swimming in the pool with your phone is not.

No, not really.

Scuba diving involves serious depths and pressures, for a start, but I’ll start with the pool example, because it (or the beach) is where so many Australians come a cropper here.

The big catch with IP ratings is that they have to be determined under lab conditions using pure lab water.

You do not fill your pool with pure lab water, and even if you did, it would quickly become contaminated with whatever’s floating by in the air, leaves, skin cells and all the other stuff that can turn pool water toxic quickly.

The solution to that to keep your pool healthy enough for you to swim in it is liberal dosing with pool salts, chlorine and all those other “interesting” pool chemicals.

None of which are covered by standard IP ratings in any way at all, and most of which are decidedly deadly for smartphone workings, because their mix of acids and bases can work all too quickly to strip down the exact protections built into IP-rated gadgets – and most certainly will over a period of time.

You’re not a great deal better off with sea water either, thanks to its heady mix of salts, industrial chemicals, bits of seaweed and of course all the junk that we’ve polluted the oceans with over the last 100-odd years.

Neither pool water or beach water should be an absolute death sentence for a phone in every time in every way, just to ward off anyone reading this who thinks “but I go swimming with my phone all the time, it’s fine and you’re full of it, Alex”…

I mean, I may be full of it from time to time (we’re all fallible, you know?), but the point here is that this kind of usage is risky in both single instances and especially over time.

On the scuba diving front, the other bit of wriggle room within these definitions relates to both depth and time. It’s variable depending on the precise test parameters, and while those should be disclosed, they’re typically going to be in the small print somewhere.

You want an example of how that can differ? Let’s take a look at the two biggest flagship phones you can buy right now, Apple’s iPhone 15 Pro Max and Samsung’s Galaxy S24 Ultra.

The S24 Ultra is a fine phone... but keep it out of the pool, OK?

They’re both IP68 rated, so they’re both the same in terms of claimed water protection (reminder: fresh lab water protection), right?

Nope.

You do have to do a little spec diving, but the Galaxy S24 Ultra is stated (as per Samsung) as follows:

Galaxy S24, S24+ and S24 Ultra are rated as IP68. Based on lab test conditions for submersion in up to 1.5 meters of freshwater for up to 30 minutes. Not advised for beach or pool use. Water and dust resistance of device is not permanent and may diminish over time because of normal wear and tear.

Source: Samsung Galaxy S24 Specifications page, small print note 39.

Whereas Apple’s definition of IP68 for the iPhone 15 Pro Max is as follows:

iPhone 15 Pro and iPhone 15 Pro Max are splash-, water- and dust-resistant, and were tested under controlled laboratory conditions with a rating of IP68 under IEC standard 60529 (maximum depth of 6 metres for up to 30 minutes). Splash, water and dust resistance are not permanent conditions, and resistance might decrease as a result of normal wear. Do not attempt to charge a wet iPhone; refer to the user guide for cleaning and drying instructions. Liquid damage is not covered under warranty but you might have rights under consumer law.

Source: Apple iPhone 15 Pro/Max specifications page, footnote 3

Samsung is very much covering itself there noting that they’re not suitable for beach or pool use – though that’s no surprise, for reasons I’ll get into shortly – but their tests only covered the Galaxy S24 Ultra to 1.5 metres, where Apple’s statement is said to be good for depths up to 6 metres. That’s quite a deep pool you’ve got there Apple!

In either case, typical scuba diving depths go considerably deeper than this, so they would not be covered. You might also note the legal disclaimers in both cases, which brings me on to my next point.

I’ve drowned my waterproof phone. What does consumer law or warranty law have to say here?

I must preface this by saying that I’m not a lawyer, and what I’m about to say does not constitute legal advice, strictly speaking. I'm just a tech journalist who's spent more than a few hours chatting about this stuff to lawyers and consumer rights advocates, that's all.

We've established that your waterproof phone isn't actually a waterproof phone, just an IP-rated water resistant phone -- but what if a manufacturer makes claims that suggests that is or could be a waterproof phone?

Here, Australian Consumer law may protect you if a manufacturer makes claims that suggest that (for example) pool or beach use is a typical usage scenario, and your device fails when you use it in that way.

This is exactly why Samsung’s water resistance claims specify not to use them at a pool or beach, by the way.

Some years ago, Samsung ran adds that suggested a number of its phones could be used that way – your typical beach scenes of people having splashy fun on beaches – in Australia, and when people complained about all the dead Galaxy phones that ensued, the ACMA stepped in, and slapped Samsung Australia with a $14 million fine for misleading consumers.

The key here is around what a manufacturer says a device can or will do, which is why whenever I’m faced with an IP-rated device, the first question I ask isn’t about what the numbers mean, but about what their Australian warranty says it covers, and then the claims they’re making around it.

Not too many are willing to go down the beach advertising route for the exact reason that Samsung got stung for it, but as an example, when I was briefed on the Shokz OpenSwim Pro recently, the very first question I asked wasn’t about depths, but about warranty coverage.

To their credit, I got the following response:

The OpenSwim Pro can be used in pools or salt water. Any issues encountered within the two-year warranty period, including from use in salt water, are covered by the warranty policy. Salt water, by nature, is more corrosive than pool water, so Shokz recommends thoroughly rinsing in freshwater after exposure to salt water.

That’s a lot more than you’ll see in the warranty documents of most tech firms, though it does make sense for a product that so explicitly has “swim” in its name.

Of course there is interpretative wriggle room here, too.

As an example, GoPro made its name with surfing-friendly cameras.

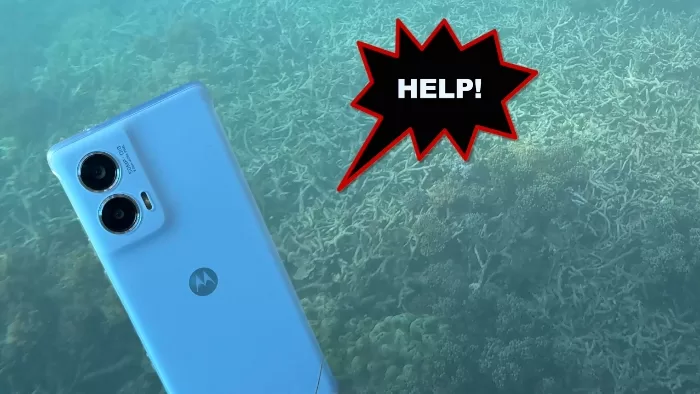

You know, the type you might test out on the Great Barrier Reef for a video... oh look, here's one:

Here's the interesting bit about that. Cameras like the GoPro Hero 12 Black are very much advertised with water activity in mind, but the only copy of GoPro's Warranty information I can find includes this disclaimer:

Because of possible user resealing errors, this product is not warranted against water housing leakage or any resulting damage. Please review and follow the instructions carefully when sealing the water housings!

Source: GoPro Warranty documents on GoPro website

As such, my Barrier Reef dive, while well within the claimed specifications of a GoPro and very much of the style that the brand has been built on, wouldn't be covered by its standard warranty if something went wrong, at least as per GoPro's interpretation.

That may come down to a question of specific proofs given the way GoPro cameras use sealed compartments for protection, and it may be that GoPro handles these a little differently for Australian consumers -- I've reached out to GoPro for any clarification they might want to supply. Australian Consumer Law would tend to suggest that within reasonable bounds it would be covered, and that might be an interesting legal tussle to get into.

The short form of this, however, is that it pays to read the warranty documentation and be aware of your broad rights (and obligations) before you dive into the pool.

Don't assume that just because a phone has a level of water resistance that it's automatically a waterproof phone, or that it always will be.

Was this useful to you? Support independent media by dropping a dollar or two in the tip jar below!

My wife killed a mobile byhaving it in a bag with a towel wrapped around her wet bathers, wet with salt water.

Immersion in 1.5m of still water is far less pressure than the transient pressure as you insert your hand into the water!

Splashing increases the pressure a lot.

They really, really should use salt water to do the IP tests for consumer goods. Pure water is so non-corrosive & non conductive it’s a cheat.

Salt water would be good, but I can see the issues with using it — for a start there’s standards in place for IP testing and you’d have to rejig those and *then* define matters like the salinity of water, and *then* there’d be the issue of how you build in salt water resistance, how long it lasts (everything corrodes eventually) and so on.